UPSTREAM

THE QUIET VOICE OF COLLECTING ON THE RIVER THAMES

Sally Hampson in collaboration with Jane Wildgoose

EXHIBITION AT TRINITY HOSPITAL, GREENWICH, 2001

| | (Click on images to enlarge) |

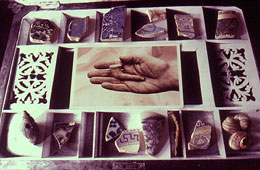

Upstream was one of a hundred projects in the London region supported by London Arts in association with the Arts Council of England under their 'Year of the Artist' programme. The project was inspired by chance meetings with members of the public and other artists while "collecting" on the banks of the River Thames.

Through a series of trips to the river banks between Woolwich and Hampton Court, Sally Hampson and Jane Wildgoose met members of the public and other artists who made contributions, sharing their experiences of collecting and of the life of the River.

The project was a development of Sally Hampson's interest in journeys, collections and curatorship. Sally was born in London, and has always been drawn to the river: a great source of fragments. Since 1995 Sally has curated exhibitions of anthropologist and explorer Kitty Lake's expeditions - narratives pieced together from fragments of journeys to Egypt, the Rishmoo Islands in the West Pacific, and the West Coast of Ireland. Sally invited Jane Wildgoose to collaborate with her on Upstream; Jane grew upon the South Coast of England, where she started beachcombing as a child, and her own collecting has developed into a fascination with the history and formality of early cabinets of curiosities. She also includes extensive research into literature in her work, and for Upstream she researched into Dickens's Our Mutual Friend for a written piece in response to the project. Themes of the River in the book, and also the way in which Dickens assesses relative values - particularly in the accumulation of wealth from discarded items - became central to her approach to the project.

Upstream culminated in an exhibition at Trinity Hospital in Greenwich; the artists would like to continue Upstream at further locations.

Contributors:

Contributors:

Katie Acornley Bill Blythe Rapahael Cohen Jim Eaton Charm Eberlé Ron Goode Billie Hakinson Clare Hampson Gerry Hastings Maurice Horhut Paola Junqueira Caroline Marais Mike Webber Fuchsia Wildgoose

Particular thanks to:

Caroline Marais at the Pumphouse Museum Rotherhithe

& Mike Webber at the Museum of London

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me. 1

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me. 1

I often wonder what makes people collect objects. Is there a reason in back of the urge to amass things? It is interesting to speculate on the origins of collecting, for a museum, quite besides its utility as a centre for research and teaching, represents the fruit of a multitude of private collections. 2

Why do I search? I want to find the history of the area [Rotherhithe]. If I didn't live so far away now I'd still go collecting: it's the excitement of finding something different.

Fossils; Anglo-Saxon coins back to 710; plenty of copper nails where they used to repair the barges and boats; live ammunition, musket balls. Coins, jewellery, rings; dockers' tools and shipwrights' tools. Tools used by lightermen. Fossils; bottles; clay pipes. Anything that was thrown in or lost. Frames of pattens; wig curlers in clay. Tokens, lead seals - customs seals from off the cargo; bullets; pewter spoons; buckles from shoes; buttons. 3

I've got pennies going back to the 17thc. We've got Roman coins as well. My father started collecting them off the dredgers and he used to say to the lads working on the dredgers: "If you find any coins I'll buy them off you, hence we've got a huge collection of Roman coins...The axehead I loaned out to the Museum of Kingston upon Thames - my birthplace. The Roman spearheads were taken by the Thames Water Authority. I've collected anything to do with the River Thames. I've got books going back over 100 years from my father - of rules and regulations on the Thames. 4

I actually found a whole sack of mail once, which I got the police to come and take away.

It's not treasure: it's stuff that's been lost. Obviously the ground in the Thames changes from time to time so you've got to keep doing it all the time to keep up with it.

There's a lot of rubbish mixed up with the good stuff as well. Unlike on dry land on archaeological sites: in the river it's all mixed up; you've got today's coins mixed up with Georgian, Roman...

You look in the bare patches which the tide has turned over, and because you can't look under every stone. And you get to know your best spots so you go to those each time - and each time something comes out.

It took me 6 months at least to teach myself what I was looking for, looking at: where to look and how to look, and the type of ground I was looking at.

The spring tides are always the best; but the best finds are luck more than experience. 5

I grew up in London, and have always collected on the Thames. It's the wildest place that I know... a place where you can get close to nature in the city, and you're dictated to by the tides. I used to meet people down there: I met a mother and son collecting blue glass. I met a man collecting coal in front of what was the old power station which is now Tate Modern - it was his heating for the week. That left an impression. 6

"It's my belief you hate the sight of the river."

"I -I do not like it, father."

"As if it wasn't your living! As if it wasn't meat and drink to you!"

At these latter words the girl shivered again, and for a moment paused in her rowing, seeming to turn deadly faint. It escaped his attention, for he was glancing over the stern at something the boat had in tow.

"How can you be so thankless to your best friend, Lizzie? The very fire that warmed you when you were a babby, was picked out of the river alongside the coal barges. The very basket that you slept in, the tide washed ashore. The very rockers that I put it upon to make a cradle of it, I cut out of a piece of wood that drifted from one ship or another." 7

There is another class who may be termed riverfinders, although their occupation is connected only with the shore; they are commonly known by the name of 'mud-larks,' from being compelled, in order to obtain the articles they seek, to wade sometimes up to their middle through the mud left on the shore by the retiring tide. These poor creatures are certainly about the most deplorable in their appearance of any I have met with in the course of my inquiries. They may be seen of all ages, from mere childhood to positive decrepitude, crawling among the barges at the various wharfs along the river; it cannot be said that they are clad in rags, for they are scarcely half covered by the tattered indescribable things that serve them for clothing; their bodies are grimed with the foul soil of the river, and their torn garments stiffened up like boards with dirt of every possible description. 8

She appeared dressed in very short ragged petticoats, without shoes or stockings, and with a kind of apron made of some strong substance, that folded like a bag all round her, in which she collected whatever she was fortunate as to find. In these strange habiliments, and her legs encrusted with mud she traversed the streets of this metropolis. Sometimes she was industrious to pick up three, and other times four loads a day; and as they consisted entirely of what are termed round coals, she was never at a loss for customers, whom she charged at the rate of eight pence a load. In the collection of her sable treasures, she was frequently assisted by the coal-heavers, who when she happened to approach the lighters, would, as if undesignedly, kick overboard a large coal, at the same time, bidding her, with apparent surliness, to go about her business. 9

Working on Upstream over a period of a year gave Sally and Jane time to reflect on and discuss the issue of collecting and collections, and the value that they are given: from a small handful of pebbles collected, which hang around in the bottom of your pocket until you find a suitable place to display them, to Mark Dion's 'Archaeology' collection now sitting in boxes at the Tate waiting to be displayed.

Notes

1. Newton, Sir Isaac, 'Brewsters' Memoirs of Newton', vol. ii, ch. 27, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Oxford University Press,1964, p154

2. Ripley, Dillon, The Sacred Grove, pl7-23

3. Goode, Ron, interview with Jane Wildgoose, 16 Feb. 2001

4. Hastings, Gerry, interview with Sally Hampson & Jane Wildgoose, 16 Oct. 2000

5. Goode, Ron, interview with JW

6. Hampson, Sally

7. Dickens, Charles, Our Mutual Friend [1865], ed. with introduction by Adrian Poole, Penguin Books, 1997, p15

8. Mayhew, Henry, Mayhew's London, ed. Peter Quennell, Bracken Books, 1984, p 339

9. Kirby's Wonderful & Eccentric Museum; or, Magazine of Remarkable Characters including all the Curiosities of nature & art from the remotest period to the present time, from the most authentic sources vol. iv, London 1820, p 859/60

Links:

|